Vito Acconci's career began in creative writing, but over the past forty years, it has expanded to include photography, printmaking, performance, video, installation, sculpture, design, and architecture. After receiving his BA in literature from the College of the Holy Cross in 1962 and his MFA in writing and literature from the University of Iowa in 1964, Acconci became a published poet, focusing on the page as a space in which words facilitate the movement of the writer and reader. By the end of the decade, however, his interests had evolved to the movement of the body and the exploration of the self in space.

His early performances were formally simple, but psychologically complex. For example, in the three-week span of _Following Piece_ (1969), Acconci followed random passersby in New York City until each person entered a private space. Meanwhile, a third party took photographs as Acconci kept a detailed log of events. Likewise, _Seedbed_ (1971), arguably his most (in)famous piece, transgressed the usual boundaries between audience and performer, as well as public and private space. During the three-week-long performance, Acconci masturbated while lying underneath the floor of the Sonnabend Gallery in New York for eight hours each day. As people walked overhead, they listened to his sexual fantasies, which were broadcast via loudspeakers.

Acconci also engaged in video work during the 1970s, a direction that initially emerged from a desire to document his performances, but he was also drawn to the self-reflexive potential of the medium. Subsequently, his work gradually moved toward a focus on the psychology of interpersonal relations. Among his highly charged films is _Face-Off_ (1973) in which Acconci plays an audio recording of himself disclosing personal details about his life. When the account becomes too revealing, however, Acconci yells, “No, No, No! Don’t say this! Keep this out!” and so on, to drown out the sound of his voice and prevent disclosure of his earlier confessions. As he invites and then impedes the viewer, Acconci is ironically candid about the extent of his anxiety over the secrets of his past.

By the 1980s, Acconci’s career had shifted to a new, related interest in public art and space. He turned to interactive sculptural work and installation pieces that include small-scale house-sculptures and furniture made from such disparate materials as dirt, tree branches, and trash cans. Design and architecture were a natural extension of Acconci’s interest in the body’s relations to space, and he eventually founded Acconci Studio with a group of architects in 1988. Together they designed experimental public buildings and sculptures in Tokyo, New York City, Russia, and Austria, among other places. Having established himself as a major figure in the field, in 1997 he was honored with a lifetime achievement award by the International Sculpture Center. That recognition—along with others from the American Academy in Rome, Berlin Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, the Guggenheim Foundation, the New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts—reflects a long career that was established with candid interactions between himself, the camera, and the viewer, as seen in _Theme Song_ (1973).

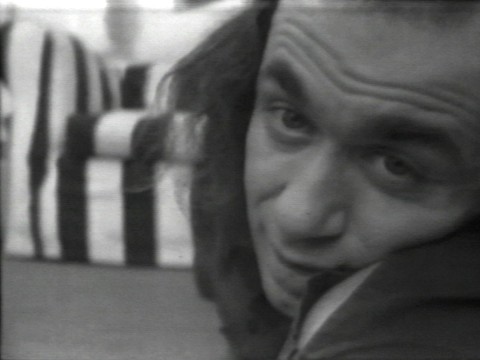

In that spare yet compelling work, Acconci lies on his living room floor, his face within inches of the camera, and launches into a thirty-minute stream-of-consciousness monologue in an attempt to seduce the viewer. Accompanied by the music of the Doors, Bob Dylan, and Van Morrison, as well as more than a few cigarettes, Acconci appeals to the viewer in a predictable but persistent manner. He claims, "I need it, you need it.... We both need it.... Just fall right into me... No one has to know about it.... All that counts is now….” During his pleading, the music stops, prompting Acconci to change cassettes at regular intervals. Thus, the viewer becomes aware of not only the production of the video, but also of the cultural notions of romance reflected in the songs.

Acconci’s come-ons are reminiscent of not only popular music but also of Hollywood movies, TV commercials, and web-cam confessionals. _Theme Song_ was ahead of its time; while its intimate style of production might be familiar to a post-Internet audience, nothing like it had been seen before 1973. It would be several years before the advent of “camgirls” and late-night “1-900-number” TV ads, both of which Acconci seems to mock in the piece. He thus turns the lens onto viewers and suggests they reconsider the strategies of seduction at play in both private and public spheres.

As Acconci is fully aware, his proposals are in vain and the viewer will not “come inside”—he is clearly acting. Nonetheless, his performance shifts between vulnerability and manipulation, causing the viewer to wonder: Is this a cautionary tale? Is it a shameless act of desperation? Or is it a revealing look into desire and loneliness? The “theme songs” playing in the background become devices that further reinforce the ambiguity of the scene. As Acconci playfully yet profoundly weaves popular lyrics into his clichéd lines, he lessens the sense of sincerity, but he also affirms the universal nature of the fear of loneliness and the search for companionship. _—Kanitra Fletcher_