“What is the relationship between how our bodies know things and how we embody our knowledge through our actions and touch? What is the relationship between that and language?” These and related themes and questions are continually raised by artist Ann Hamilton in large-scale, multimedia installations, as well as videos, photographs, and performances. She frequently incorporates handwritten texts or spoken language from a wide range of writings—poetry, single words, cultural and literary criticism, and even a laundry ledger. Hamilton also often includes a living presence in her work. Plants, animals, or humans appear, and the latter typically completes a task, reads various statements, or repeats a particular gesture or hand movement. Together or separately, these different figures continuously (re)create the pieces, giving ongoing life to each of Hamilton’s artworks.

Born in Lima, Ohio, in 1956, Hamilton received a BFA in textile design from the University of Kansas in 1979 and an MFA in sculpture from the Yale School of Art in 1985. From 1985 to 1991, she taught at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Currently she resides in Columbus, Ohio, with her son and husband, Michael Mercil, also an artist, and serves as a Distinguished University Professor in the Department of Art at Ohio State University. During the past thirty years, Hamilton has received numerous honors, including the MacArthur Fellowship, NEA Visual Arts Fellowship, Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award, Skowhegan Medal for Sculpture, Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship, and the National Medal of the Arts. She also represented the United States in the 1991 Sao Paulo Bienal and the 1999 Venice Biennale.

Hamilton’s first solo exhibition, ground (1981), evoked her early training as a textile designer. In the Walter Phillips Gallery in Banff, she surrounded the space with one- to two-foot lengths of telephone wire. Each square foot of the walls and floor projected an intimidating yet captivating surface. Likewise, Hamilton’s toothpick suit (1984)—a men’s thrift-store suit covered with layers of toothpicks in porcupine fashion—was both fearsome and awesome. The artist wore the construction as viewers walked around but did not interact with her. Hamilton also had herself photographed in the suit to begin her body object series of images, which feature her wearing a range of constructions.

toothpick suit would be a fateful work for Hamilton as her various deployments of the piece would be reflected in later projects that also combine multiple approaches, including installation, object-making, performance, and photography. Furthermore, Hamilton would find ways to engage or evoke multiple senses—sight, sound, smell, touch, and even taste—with a dense accumulation of material as seen in ground and toothpick suit. Using tables, books, mirrors, windows, clothing, and fabric, she would produce immersive experiences in response to not only the formal qualities but also the social and political histories of the various sites in which she creates her art.

Still, the word and the body animate and articulate Hamilton’s interests, as seen in indigo blue (1991), an homage to labor set in South Carolina. For the performance installation, she assembled an enormous pile of 47,000 used blue work uniforms and hung sacks full of soybeans on the walls. For the duration of the piece, a live “attendant” sat at a table and erased printed text from books. The shavings from the eraser accumulated within the pages of the books and the sacks of beans slowly spilled and began to sprout, aided by the humid air.

tropos (1993) also involved the erasure of words from a book, this time with a heated electric burin. The attendant sat at a desk burning away the text, leaving a pungent smell in the air, which combined with the aroma of the interwoven horse hair that covered the entire floor. All the while, a barely audible recording of an incomprehensible voice would intermittently play throughout the space. Rather than the content or words spoken, Hamilton focused visitors’ attention to the texture of the sound.

Hamilton’s more recent installations have entailed the participation of visitors. For the event of a thread (2012) she hung a field of swings from the rafters of New York’s Park Avenue Armory. The swings were counterbalanced by an enormous white silk curtain that would rise and fall, sway, and ripple as visitors swung. Alongside this activity, a writer sat at a desk composing sentences, cooing caged pigeons were released at the end of each day, and two actors read selections from different texts, which were broadcast on radios wrapped inside paper bags that were available for visitors to carry throughout the space. As the artwork changed each day, all of the activity was taped, and the recording was played back the next day.

Hamilton’s project for The University of Texas at Austin, O N E V E R Y O N E (2017), involves public participation as well. She photographed more than 500 volunteers through a frosted semitransparent film that rendered touch visible to evoke the relation between contact and caring. That which made contact with the surface comes into sharp focus and the rest of the gauzy frame veils the figure in an ethereal manner. (The 21,000 images Hamilton captured are used in multiple forms, including a website, newspaper, 900-page book, and 71 porcelain enamel portrait panels installed in the Dell Medical School.)

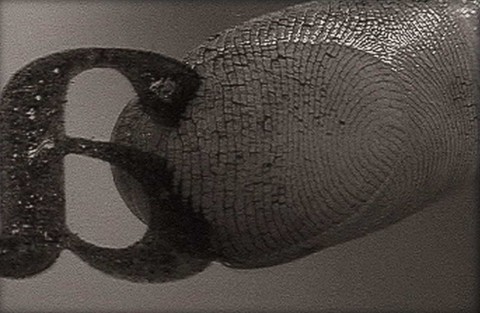

abc·video (1994/1999) also depicts touch in a way that recalls the core of Hamilton’s practice—the interconnection of the body and the word. Hamilton presents an extreme close-up of a wet fingertip pressed against glass. The amoeba-like form slowly absorbs and erases the letters of the alphabet, which have been stamped onto the pane. As ink from the characters fills the lines of the fingerprint, language effectively enters the body. The orb of the finger then appears to rewrite the script as the video loops backward.

With each movement, text dissolves into touch and vice versa, and these elements seem to become one or interchangeable. The erasure of the letters—characters that are the foundation of a language—by an individual’s hand, followed by the seemingly magical emanation of text by the same means, evokes the inextricable tie between the human body and communication.—Kanitra Fletcher