Often called the "Evel Knievel of contemporary art," Chris Burden became well known for his simple, but extreme, performance pieces of the early and mid-1970s in which he was cut, shot, kicked, locked up, crucified, nearly drowned, and electrocuted. By the late 1970s, his work had shifted from the ephemeral toward monumental sculptures and large-scale installations. However, over the past forty years, Burden’s work consistently has reflected social environments, commented on cultural institutions, and addressed the shifts and boundaries of science and technology. In particular, against a backdrop of violent images in mass media, and the distancing, desensitizing effect of media in general, Burden’s art viscerally portrays the realities of pain, danger, and anxiety to his audience.

Burden’s practice is concerned with limits. In various, often shocking, ways he has looked at and tested them, thereby putting himself in extreme situations through which he suffers. Yet, as Randy Kennedy writes, “His approach to the performances was always more about method than shock: a systematic what-if exploration of the limits of the human body, of violence, of authority, of mortality and of a kind of nonreligious transcendence.” Beginning with Five Day Locker Piece (1971), his master's thesis at the University of California at Irvine, he locked himself into a 2-by-3-by-3 foot locker for five days and nights with a five-gallon jug of water in the locker above him and, for practical purposes, an empty five-gallon container in the locker below.

Shoot (1971), arguably his most (in)famous piece, resulted in Burden being shot in the arm with a .22 rifle. (The shooter was supposed to nick the side of his arm, but missed.) Performed during the height of the Vietnam War, Shoot was meant to resensitize people to the violence they passively and frequently observed on television in the comfort of their homes. Furthermore, Burden explained: "I had an intuitive sense that being shot is as American as apple pie. We see people being shot on TV, we read about it in the newspaper. Everybody has wondered what it's like. So I did it."

In Doorway to Heaven (1973), Burden nearly killed himself when he touched two live electric wires to his chest, but he crossed them in time so that only sparks erupted. For another well-known piece, Trans-fixed (1974), Burden nailed his palms to the back of a Volkswagen Beetle. The car then ran at full speed for two minutes before being pushed back into a garage. Doomed (1975) was another enduring challenge for Burden and his audience. He laid beneath a 5-by-8-foot sheet of plate glass in a gallery for 45 hours until a museum employee brought him a pitcher of water. Unbeknownst to the staff, who did not want to disturb him out of respect for his process, Burden actually was waiting for someone to intervene in order to end the piece.

Eventually Burden moved away from body art toward massive, powerful objects and soundly ordered installations that often refer to, or replicate, cars, ships, bridges, buildings, airplanes, and submarines. Nonetheless, Burden considers these works performative as well. B-Car (1975) was a lightweight automobile designed to run 100 miles on one gallon of gas. The potentially dangerous The Big Wheel (1979) was a three-ton, eight-foot, cast-iron spinning flywheel powered by a motorcycle.

Ironically, many of his imposing works are made from toys and other small objects. In the summer of 2008, Burden presented What My Dad Gave Me—a 65-foot-tall skyscraper made of approximately one million stainless-steel replicas of Erecter set parts that stood in front of Rockefeller Center in New York. While the piece has a playful quality, the diminutive size of its components also conveys a sense of danger—theoretically, if one piece breaks or is out of place, it all comes down.

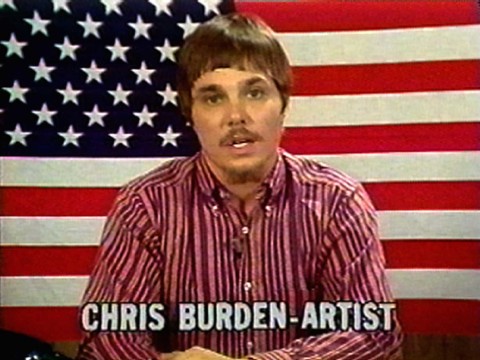

Unexpected disruption has colored Burden’s video work since 1974, when he began using the medium as a component of, and way to, document his performances. Both of these uses were entailed in the production of The TV Commercials (1973–77). Landmarks Video will present Burden’s compilation of his four legendary television interventions, which he produced in 2000. Along with a re-presentation of each “advertisement,” Burden’s anthology includes onscreen text detailing his motivations for, and the conditions of, the airings. Included are Through the Night Softly; Poem for L.A.; Chris Burden Promo; and Full Financial Disclosure.

At once humorous and subversive, Burden’s TV Commercials varyingly refer to the ways in which television influences behavior, namely how it sanctions passive voyeurism and deference to authority. Instead of pitches for products, viewers see Burden crawl on his stomach through broken glass or reveal his gross income, expenses, and net profit in 1976. By disassociating viewers from TV’s disassociation from reality, Burden was able to take advantage of the medium’s powerful communicative potential while also momentarily disrupting its form and effect on viewers. —Kanitra Fletcher