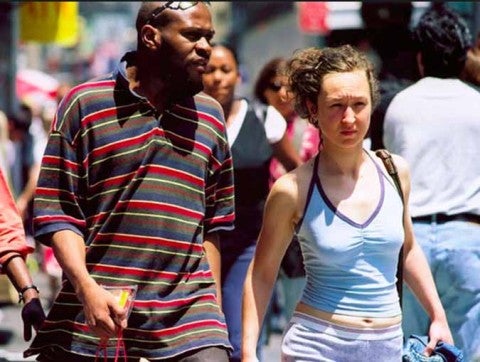

Since the early 1990s, Beat Streuli has used the urban environment as a stage, focusing his lens on the inhabitants of cities across the world in videos, billboards, life-size color photographs, multi-slide installations, and large-scale window installations on the facades of public buildings. Born in 1957 in Altdorf, Switzerland, Streuli attended the Schools of Design in Basel and Zurich and the Hochschule der Künste in Berlin, where he lived until 1987. As a student, he concentrated on abstract painting and installation art until the late 1980s, when he had residencies in Paris and Rome. In these two capitals, Streuli developed further interest in photography and figuration. He then moved his base to Düsseldorf in the 1990s and developed the style of street photography for which he is known. His images depict what he calls “‘the glamour of the usual’—people walking the streets in familiar states of pedestrian reverie, photographed with professional care (‘glamour’) but without drama (‘the usual’).”

Streuli has captured individuals in crowds, passing through public spaces and engaged in the quotidian tasks of life on the streets of New York, London, Brussels, Moscow, Dubai, Athens, Sydney, Cape Town, Tokyo, and Buenos Aires, just to name a few. He has had solo exhibitions at ARC / Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (1996); Tate Gallery, London (1997); Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (1998); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2000); and Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2002). Permanent installations of Streuli’s photographs are mounted at the Lufthansa Aviation Center at Frankfurt International Airport, Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, and Triemli Hospital, Zurich. He also has participated in the Sydney, Johannesburg, and Gwangju Biennials.

Streuli’s still images are shot with a telephoto lens on unsuspecting subjects. By using harsh or bright sunlight, he creates high-contrast pictures in which the background often turns black. The individual thus appears removed from their context. Despite having been merely standing at a crosswalk, waiting for a bus, or involved in some other inconsequential activity, Streuli’s subjects have dramatic presences augmented by the large-scale format of his photographs.

Numerous examples are on display in Streuli’s multi-slide installation Oxford Street (1997). The slide show comprises portraits of anonymous persons immersed in the clamor of London’s crowded thoroughfare. Rather than the shops and service outlets, however, Streuli focused his lens on the facial expressions and everyday gestures of individuals, eight of which can be seen simultaneously in the installation. Multiple images also overlap or are juxtaposed with others in various spatial configurations, thus reinforcing the experience of the dense crowds that occupy Oxford Street.

Streuli’s practice would soon incorporate video. Like his photographs, the videos also show preoccupied passersby as they go about the business of daily life, walking the streets immersed in their own thoughts and with apparent purpose. Streuli also continued to use a telephoto lens, which enables him to keep a distance, to observe from afar. Moreover, as he captures multi-ethnic crowds, the seeming objectivity of his presentations is instrumental in their interpretation. That is, Streuli does not exoticize his subjects or force a sociopolitical reading on the heterogeneity of the inhabitants passing through his videos. His work simply documents and underscores the ordinariness of realities. As Streuli says, “In my work, I have simply tried to deal with what’s on my doorstep wherever I have lived or spent some time. I was hardly ever searching for something, rather trying to avoid ‘intentions’ and work in some sort of an ‘écriture automatique’ kind of way.”

The Pallasades, Birmingham 05-01-01 9 (2001) exemplifies Streuli’s approach as it captures a river of humanity in the Pallasades Shopping Centre in Birmingham England, one of the youngest and most multi-cultural cities in the world. The mass movement of bodies ripples like a wave across the frame. There seems to be no end to the number of shoppers, who carry bags, talk on phones, and take photos as they wait at lights and cross streets, walking directly toward the camera.

This throng of figures moving in the same direction suggests the universality of human experience. At the same time, Streuli does allow for moments of individuality to emerge. Certain people are taken out of their relative anonymity and become central characters, particularly those who pause or linger within the sea of pedestrians that flows around them. Because the projections are in slow motion—33 percent of real speed—and because Streuli uses a telephoto lens, viewers also can follow an individual for long stretches of time and catch subtleties of gestures and facial expressions that would normally go unnoticed. This is a critical feature for Streuli, who states, “It’s true about the crowd and its anonymity, but it’s also the intimacy that comes with it that allows for more indulgent people-watching freedom. The number of people you actually meet and talk to is very limited. Watching is an important way to get the ‘broader picture.’”

Ironically, viewers “get the broader picture” with a narrow view of New York City in 8th Avenue/35th Street (2002). Streuli positioned a camera on the sidewalk at a busy intersection near Penn Station, where it remains fixed at this spot as a diverse mix of pedestrians as well as vehicles pass through the frame. From time to time somebody lingers on the corner, but by and large people pass by in various directions. At times, the corner is blocked from view by the backs of people, waiting to cross the street. When this happens, the camera remains unmoving. Its telephoto lens also gives a longer focal length, a narrower field of view, and a magnified image, making passersby appear densely packed and reinforcing the senses of congestion and bustling activity.

While the anti-theatricality of Streuli’s video has been noted by critics, there are suspenseful moments in 8th Avenue. In first half of the video, a woman stands across the street waiting and searching for something. She lingers for an uncomfortably long period, and one cannot help but wonder why and if she will find what she is looking for. She becomes a temporary protagonist of a narrative that never is concluded, as she eventually disappears from the scene. Later she effectively is replaced by another woman, who apparently is lost. She stands at the corner staring into space, at a piece of paper, and in different directions. After much deliberation, she vanishes from the scene, only to return and pass through in the opposite direction just as the video concludes.

These activities are accompanied by a soundtrack of voices, horns, and other noises of a city street, the sources of which are never identified. The sounds come from outside the frame or far from the subjects on screen, which conveys the larger context and great extent of activity on the streets of Manhattan that is restricted from view. Indeed, Streuli typically offers little visual cues to differentiate his settings. The titles are the only information that indicates the locations. Nonetheless, while he removes the structural, architectural elements that make each city unique, Streuli’s imagery asserts that it is the human elements—the people—that give each city life. – Kanitra Fletcher