After graduating with an MFA from the University of California, Davis, in 1966, Bruce Nauman garnered attention through his neon wall reliefs, interactive sculptural installations, films, and videos. He was part of a new generation of artists whose process was driven by concepts, materials, and situations. Whether working with words in signs, with body parts in sculpture, or with people in film or video, for more than forty years Nauman’s underlying concern has been how a body makes, experiences, and perceives art.

One of Nauman’s best-known works is also one of his earliest. It is a wall- or window-bound neon sign from 1967 that spells out _The True Artist Helps the World by Creating Mystic Truths_ in an electric blue and red spiral. Made in a former grocery store that become Nauman’s San Francisco studio, the gesture uses the arresting yet ubiquitous language of advertising to challenge the goals of its maker and its own profundity. Depending upon one’s interpretation, the sign either dramatically deflates or elevates the role of artists and art in society. It follows the Duchampian tradition—of making the everyday a focus of art—engaged by John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Andy Warhol, and others who were influencing Nauman’s development at the time.

Many of Nauman’s works have been influential, yet his numerous non-narrative, performative films and videos from the late 1960s have played a particularly significant role in art history. They have shaped how we think about art at a time when avant-garde artists were using newly available equipment to make short films and videos, many of which featured the body as the subject. From 1967 through 1969, Nauman produced at least sixteen 16mm films and twelve videotapes. Influenced by Samuel Beckett’s startlingly restrained focus on the human condition, most of these feature the artist repetitively performing quotidian tasks, such as bouncing a ball or walking on the perimeter of a square taped on the floor. When the task is complete, the film or video ends.

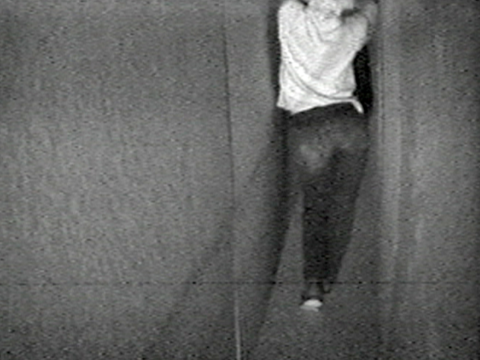

_Walk with Contrapposto_ (1968) is one of the best-known examples of Nauman’s videos. In the hour-long, black-and-white videotape, Nauman slowly walks up and down a narrow corridor built in his studio, creating a repetitive, predictable motion. The video is meant to be revisited over time like an object rather than watched from start to finish like a film. Because there is no climax and the camera does not capture the artist’s face, the central focus becomes the sound of Nauman’s heavy footsteps and the sight of his body. For the duration of the task, Nauman keeps his arms raised and hands clasped behind his neck, which draws attention to his body—specifically how he pauses with each step and throws his hips into the type of contrapposto stance historically used by Western painters and sculptors to study the human form. In this performative video, Nauman becomes a moving, twentieth-century version of a piece of classical sculpture. Using just his body, he draws upon art history past to make a work that says much about, and contributes to, the art history being made in the present. _—Kate Green_