Born in Bogota in 1946, Miguel Ángel Rojas’s artistic practice has established him as an influential force in and beyond Colombia. Through a range of approaches, including intrigue, displacement, and juxtaposition, Rojas challenges viewers to take notice of largely unseen social interactions and political connections. He has worked in several mediums—engraving, drawing, and intaglio—but his practice has been shaped greatly by his lengthy venture into photography from the late 1960s through the 1970s.

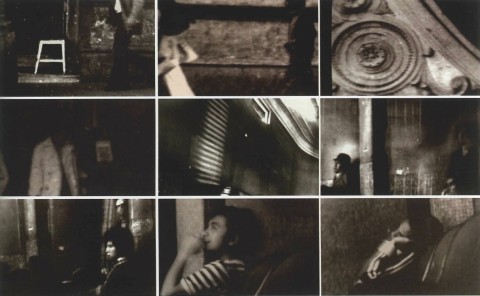

He embraced the camera, even though photography was not considered an accepted fine arts medium at that time. It allowed him to pursue not only art-making outside of the studio but also unconventional subject matter. In particular, from 1973 to 1979 he explored margins of society in a series of photographs. By hiding his camera in a bag or on his person, Rojas captured sexual encounters between gay men cruising in B movie theaters throughout Bogota. The lack of light, focus, and composition of the ghostly imagery underscored the suppression and relegation of the gay community.

The series also highlights concerns Rojas has had throughout his career. Much of his work has dealt with issues of identity, subjectivity, and especially marginality, a topic he continued to explore in unconventional ways, including through drug usage. In the mid-1990s, Rojas began using coca and other substances to examine histories of pre-Columbian indigenous cultures. He explains: “My use of intoxicants is … part of an artistic strategy that is also political. It is political in that the hallucinogens that I use are part of…indigenous traditions. These traditions are marginalized, not because they are illegal but because they are associated with the social periphery.”

Rojas’s work eventually reflected the evolution of coca leaves from the periphery to the center of major cities. He created works that comment on the production and consumption of cocaine, heroin, and other narcotics that have become as trendy and lucrative as they are addictive and destructive. In the 2010s, Rojas produced text- and grid-based compositions that suggest a mapping of the damaging impact and influence of the cocaine trade on Colombia and the United States. He cut coca leaves and dollar bills into a myriad of tiny dots that he arranged on large-scale sheets of paper. Some are half-coca, half-dollar diptychs of texts that connect the sites of coca production and names of narco-traffickers and kingpins with those of cocaine consumption and celebrity addicts. In _Camino Corto_ (2010), N. Nolte, J. Joplin, S. Vicious, and several other names are inscribed in bits of coca leaves above pieces of dollar bills that spell out Gordo Lindo, Alex Bond, La Perra, and so on.

Rojas also has taken a more humanized approach to the matter. Installed between photographs of a young, healthy man named Beto and his later ravaged, drug-addled figure is _Mirando la flor/Watching the Flower_ (1997–2007), a soundless video featuring the older man, who talks about his life. The video has been sped up, making Beto’s gestures jumpy and animated as they head toward his dreadful confrontation with the photograph of his youth.

Besides the ravages of drug addiction, in intimate portraits, Rojas has explored other forms of destruction resulting from the narcotics industry. His groundbreaking video _Caquetá_ (2007) features a soldier in the jungle laboring to wash camouflage paint from his face. This seemingly simple act is made quite difficult due to the loss of his hands from an explosion in the Caquetá region of Colombia. _David_ (2005) also features an amputee, this time a Colombian soldier who lost his leg in a land mine explosion while working in drug enforcement. The nude model adopts the contrapposto pose of Michelangelo’s masterpiece _David_, thereby commemorating the numerous Colombian youths who have fallen victim to either side of the drug war. Whether inflicted by oneself or others, the devastation from the drug trade has been widespread, yet Rojas sheds light on the intimate, individual nature of the aftermath.

The intimacy of individuals is captured in another way in _Corte en el Ojo (Cut in the Eye)_ (2003). The first half of the video features Rojas’s aforementioned secretive photographs of homosexual encounters, specifically his final set of images taken in Bogota’s Faenza Theater, entitled _Faenza_ (1979). As a video sequence accompanied by a touching soundtrack, the once-ghostly pictures come alive. Rojas recreates the atmosphere of the theater with close-ups of individuals and focused views of architectural details. The furtive imagery is followed by footage taken during Rojas’s return to the same theater more than twenty years later in 2000, when he recorded his search throughout the red interior, through the new entrance, across the chairs, and up to the staircase.

The combination of these two periods becomes a poetic reflection on Rojas’s own past (including a physical assault upon being caught by one of the subjects of his photographs that resulted in his cut eye and the eventual title of the film) as well as the history of the venue. The Faenza Theater is considered a national treasure for its Art Deco architecture, which Rojas details. However, he also zooms in on his pictures of gay men that frequented the space, the past activities and experiences of which are also a part of the theater’s history. Throughout his career, Rojas has expressively revealed such aspects of society, those that have been ignored and, especially, undocumented. Thus, fittingly, a video showing the evolution of the theater poignantly ends in black and white with a look back to a lone man seated in the audience. _—Kanitra Fletcher_