Born Arlene Hannah Butter in New York City on March 7, 1940, Hannah Wilke was one of the most controversial artists of her time. Until her premature death from cancer at the age of fifty-two, she drew, filmed, sculpted, painted, and performed works that tackle gender, sexuality, and feminism. Because Wilke often displayed her own nude body in a seductive, unabashed manner in her images and performances, Wilke’s critics declared her either courageous or a narcissist, or both. In response, Wilke once said, "When people get so annoyed with content that they don't look at things formally, then it's necessary to continue."

Wilke graduated from Temple University in Philadelphia with a BFA from Tyler School of Art in 1960 and a BS degree in education in 1961. Her early works include playful, erotic imagery of abstract breasts or phalluses conflated with emphatic marks and shapes. She also debuted layered, folded forms made from latex or clay in the mid-1960s. These fortune-cookie–like sculptures are highly suggestive of female genitalia and their shape became Wilke’s signature. She went on to create numerous versions in a range of media, including wax, chewing gum, Play-Doh, erasers, cookie dough, and even laundry lint.

In 1974, Wilke began teaching sculpture at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan, where she remained as a professor for nearly two decades. Although she continued to produce both sculpture and drawings, by the early 1970s she had begun to focus on video, photography, and performance art. Wilke used these new media in ways that objectified her own body in order to comment on the history of exploitation of women in both fine art and popular culture. She also produced some of her most (in)famous works, such as S.O.S.—Starification Object Series (1974–75).

S.O.S. comprises photographs of Wilke semi-nude with vaginal-shaped pieces of chewing gum stuck all over her body that look like sores. As she mimics conventions of femininity and female beauty, Wilke also disrupts them and the pleasure of the gaze. Furthermore, her use of gum was symbolic. Wilke stated, "In this society we use up people the way we use up chewing gum. I chose gum because it's the perfect metaphor for the American woman—chew her up, get what you want out of her, throw her out and pop in a new piece."

Also representative of not only societal but also art historical forms of female exploitation is Wilke’s seminal filmed performance, Through the Large Glass (1976). In this piece, she appears in a stylish white suit and fedora and does a slow striptease in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. As she cavorts, Wilke is filmed through the glass of Duchamp’s iconic work The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, otherwise known as The Large Glass. Partially obscured by Duchamp’s phallic and vaginal objects, she teases the viewer as she sheds her pantsuit, effectively becoming both the bride and the bachelor, thereby remaining in control of the scene literally and figuratively. Nonetheless, feminist groups found it difficult to approve of or even accept Wilke's practice in her day, which perhaps prompted her creation of a poster in 1977 that read, in part, "Beware of Fascist Feminism.”

Wilke continued making videos, sculptural work, and performance art from the late 1970s to the mid-1980s. In 1987, she was diagnosed with lymphoma, and in the last few years of her life, with the help of her husband, Donald Goddard, she documented her struggle with the disease in a photographic series entitled Intra-Venus (1991–93). Arguably her most courageous work, the thirteen large-scale images unsparingly depict the gradual deterioration of her body. Wilke is shown nude, bald, and bloated in several pictures. At times, she appears exhausted and bandaged from chemotherapy and bone marrow transplants. At others, she adopts the poses she did for S.O.S. Thus, throughout her transformation and decline, she rejected any shame of her body, and displayed herself as assertively as she did twenty years earlier.

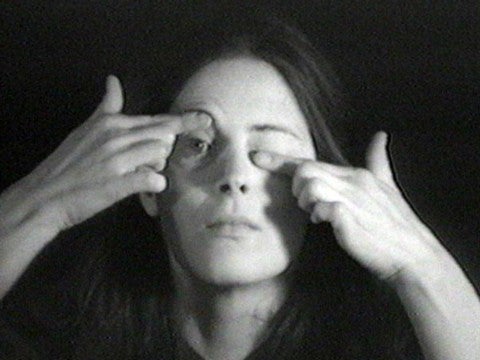

As one critic observed, “The overarching narrative theme of Wilke's career is the fragility of the human psyche and its vessel.” This view is affirmed by Intra-Venus as well as her 1974 video Gestures. In it, we see her using her skin as a sculptural material as she slowly kneads and pulls at her face. She makes expressions and gestures with her face, head, and hands, and thoroughly examines her features by patting, slapping, and stroking them. She does so for over half an hour, making the exercise more than a display of female narcissism or pleasure. The sheer length of the video figures it also as a form of torture. In fact, she smiles so hard at one point that she seems to be grimacing. Wilke therefore shows the performance of femininity and female sexuality to be the site of as much pain as pleasure. As she explained, Gestures shows “the pathos past the posing." –Kanitra Fletcher