Kent Monkman was born in 1965 and raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba, by his Swampy Cree father and mother of English-Irish descent. After graduating in 1989 from the Sheridan College of Applied Arts in Ontario with a degree in Illustration, Monkman remained in Toronto where he continues to live and work. He is an accomplished painter, sculptor, filmmaker, installation artist, and performance artist who has had solo exhibitions at numerous museums, including the Montreal Museum of Fine Art, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in Toronto, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, and the Art Gallery of Hamilton.

Monkman is known for his picturesque paintings that unabashedly call attention to the devastating effects of colonialism, particularly its impact on sexuality. His art appropriates and disrupts the visual language of Western art history as it challenges traditional depictions and perceptions of the American West. Monkman paints stunning Romantic(ized) landscapes based on those of nineteenth-century artists, such as George Catlin, Paul Kane, Frederic Edwin Church, and Albert Bierstadt. However, he explains, “When you look at these paintings as an aboriginal person, you realize how subjective they are…. [T]hese landscapes were not empty as they were painted in the 19th century…. They were actually populated by many different nations of people…. So when I make these paintings I'm not necessarily repainting history, but I'm nudging people toward seeing that there are these big missing narratives.” In Monkman’s hands, these narratives include satirical homoerotic fantasies, typically couplings of submissive cowboys and dominant young Indian braves, inserted into his vast wildernesses.

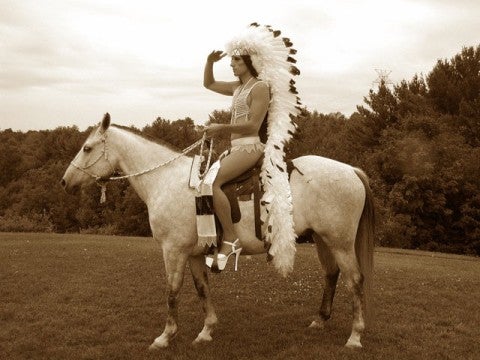

He creates a new “Old West” of crossdressing and role-swapping between “cowboys and Indians” as well as other diverse beings, including coyotes, centaurs, pegasi, shamans, artists, European explorers, traders, and, usually at the center of activities, his alter ego, Miss Chief. Monkman’s flamboyant character Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle (punning “mischief,” “Cher,” and “egotistical”) is an over-the-top drag queen Indian princess bedecked in feathers, sequins, and high-heeled platform moccasins. Her presence in and out of paintings challenges traditional gendered power dynamics and reintroduces sexual fluidity into a history of repression. Monkman, who identifies as queer, also identifies as “two-spirit,” an indigenous concept that honors the existence of both male and female spirits in one body. Miss Chief is a reference to the fact that homosexuality was accepted and even revered in tribal cultures.

Miss Chief acknowledges this reality when she appears in Monkman’s paintings, such as Artist and Model (2003). The work depicts an impeccably painted, idyllic landscape within which Miss Chief, attired in a floor-length headdress, pink stack heels, and a loincloth, stands at an easel. She coolly paints the white cowboy figure behind her, who is tied to a tree with pants at his ankles and pierced with arrows like Saint Sebastian. Miss Chief also appears in The Triumph of Mischief (2007), a seven-by-eleven-foot canvas crowded with libidinous mischief between Native Americans, European colonizers, and other creatures within a sublime sylvan setting. The image serves as a history of both Western art and colonialism, and the madness plays out before the melancholic eyes of Miss Chief.

Monkman also appears as his alter ego in videos. Shooting Geronimo (2007) features a white filmmaker dressing two young Native men in wigs and loincloths and instructing them on how to dance “authentically” for his Western. When Miss Chief intervenes, the director is shot accidentally, forcing the boys to take control of the film. In Dance to Miss Chief (2010), Miss Chief stars in the video of her club track of the same name. Interspersed with shots of her gyrations and her dancers’ amazing acrobatics is vintage footage from Karl May’s Westerns for a playful critique of German fascination with North American Indians.

Mary (2011) also stars Miss Chief as she remembers the Prince of Wales's visit to Montreal in 1860. Donned in a red-sequined dress and feathered leather boots, she holds the foot of the white symbol of power. “The influence of the church on aboriginal people inspired me to work with biblical allegories,” says Monkman, who chose the allegory of Mary Magdalene washing the feet of Christ with her hair because “It made me think of the idea of surrender in relation to the treaties…. When they were signing the treaties they didn’t think they were surrendering their land, they thought they were sharing.”

More recent works feature a cast of modernist figures from a range of artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Henry Moore. For instance, the painting Love (2014) takes place in the middle of a neighborhood street, where a group of Native men carefully insert an abstractly rendered female nude straight out of a Picasso painting into a large trash bag. Monkman’s imagery calls into question the cost of modernity while highlighting the strength and agency of those forced to adapt. His work recalls that the rise of modernism was contemporaneous to the tragic descent of indigenous life, for many, into reservations, residential schools, and general despair.

Thus, in a simulation of a daytime hospital soap opera, Miss Chief visits the Modern Wing to accompany a doctor of fine arts on his rounds to various ailing art movements in Casualties of Modernity (2014). She wears a nurse’s uniform, diamond jewelry, and seven-inch, red patent platform heels as she overlooks abstract art, performance art, conceptual art, and romanticism. On one bed lies a fractured Cubist sculpture of a female, its flattened forms gasping for life. Monkman’s video recalls how Matisse, Giacometti, and others drew upon and distorted Oceanic and African artistic traditions as they analyzed and reduced people and objects to two-dimensional planes. The modern art figures serve as a metaphor for modernity’s reduction of Indigenous cultures and their loss of identity.

Group of Seven Inches (2005) is another cheeky critique of the assimilation and appropriation of Native American culture by colonial settlers through which Monkman makes audiences aware that “you've been looking at us [but] we've also been looking at you." Thematically similar to the aforementioned painting, Artist and Model, the video presents a role reversal of sorts in a silent, grainy, black and white film that leaps back in time to rearrange colonial history.

Monkman as Miss Chief plays the part of an aboriginal explorer, approaching European subjects with a removed curiosity. She arrives on a horse and leads two European males in loincloths to a cabin where she seduces them with alcohol and uses them as figure models for her painting. She then dresses them in clothing she feels makes them appear as more “authentic” examples of the European male, rather than how they would normally appear. Throughout the film, old-fashioned subtitles display a script appropriated from the patronizing testimonies of painters George Catlin and Paul Kane, which were written during their nineteenth-century travels in the West.

The setting itself also subverts the subjectivity and authority of colonial art history, as the film was shot on the grounds of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, the premier home of art by the Group of Seven comprised of nineteenth-century painters who are among Canada’s most famous artists. The group aimed to record the nation’s rugged wilderness regions in works that have come to symbolize a distinct Canadian identity. However, their romanticized depictions of the landscapes suggest these spaces were unpopulated and undiscovered. With their misrepresentations not lost on Monkman, he flips the script in more ways than one and makes Group of Seven Inches his own racial projection fantasy, taking significant license in the present as many others did in the past. —Kanitra Fletcher