German artist Christian Jankowski is known for his conceptual and performative works that blur the boundaries between art, popular culture, and mass media. Born in 1968 in Göttingen, Germany, and educated at the Academy of Fine Arts in Hamburg, Jankowski has established himself as a significant figure in the international art world, with exhibitions across Europe, the Americas, and Asia. His works often involve humor to engage audiences and disrupt expectations. They are frequently collaborative, involving individuals and institutions outside the traditional art sphere from diverse fields such as television, religion, or commerce.

Throughout his career, Jankowski has addressed the role of belief—both religious and artistic—in shaping culture. By collaborating with figures such as televangelists and fortune-tellers, he explores how meaning is constructed and who has the authority to define it. In 1999, he created Telemistica, for which he learned Italian and called in live to five Italian TV fortune-tellers, asking them to predict his future as an artist and forecast the success of his contribution to the 48th Venice Biennale (which was Telemistica).

The Holy Artwork, created in 2001, continues his questioning of the role and interpretation of art in society. Developed in collaboration with Pastor Peter Spencer at the Harvest Fellowship Church in San Antonio, Texas, The Holy Artwork was commissioned as part of a two-month residency at ArtPace, also in San Antonio. There, Jankowski observed a preponderance of Christian programming on Texas television. The work was further inspired by Spanish Baroque religious paintings, particularly Juan Bautista Maíno's Saint Dominic in Soriano Ri, which features an angel taking up the brush of the painter who appears to have suddenly died.

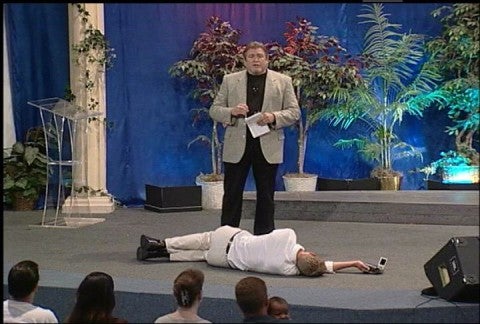

During the church’s televised Sunday service, Jankowski collapses at the pastor's feet, remaining prone as Spencer delivers a sermon connecting artistic creativity and divine inspiration. The pastor informs the congregation and television audience that they are witnessing a “holy artwork,” blending religious ritual and performance art. Spencer discusses the indivisibility of artistic creativity and God’s creative force, after which the church’s “Praise Team” performs worship music. Spencer then leads a final prayer in which he thanks the lord for creating video and suggests that contemporary art can act as “a bridge between art, religion, and television.” The piece concludes with Jankowski rising to his feet and returning to his seat, raising questions about the sanctity of art, the function of mass media, and the spectacle of religious entertainment.

The Holy Artwork also highlights Jankowski’s willingness to relinquish control over aspects of his work. He did not have a say in the final sermon; furthermore, his face is never seen. Instead, the piece unfolded through conversations between the artist and minister prior to the performance and depended on the congregation’s activities. This openness to unpredictability fosters dialogue between art and its context and encourages audiences—both in church and in gallery settings—to reflect on their own assumptions about authorship, originality, and authenticity in contemporary art, while playfully critiquing the mass-media spectacles produced by the religious entertainment industry.

As in much of Jankowski’s art, meaning emerges from the process itself, remaining open-ended and subject to viewers’ interpretations. He has said, “If you lose control, if you don’t know exactly what the artwork wants to tell you, or the meaning of it—that’s the moment you have to start thinking yourself and you don’t come down to common sense.” The Holy Artwork allows for such free, undefined contemplation. It represents a dynamic inquiry into the intersection of art, religion, and mass media, questioning the boundaries of artistic production while reflecting on the broader cultural processes that shape our understanding of creativity and belief. —Kanitra Fletcher