Born to European immigrants in National City, California, John Baldessari learned perseverance from his parents at a young age. This lesson has served him well throughout his career as he has continually sought ways to redefine and reinterpret art. A progenitor of conceptual art, Baldessari has described his works as “what I thought art should be, not what somebody else would think art would be.”

This determination led to an illustrious career. Baldessari earned a BA and an MA from San Diego State College and studied at the University of California, Berkeley, the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and the Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles. For more than twenty years, he led innovative classes at CalArts in Valencia, California, and in 1986 he was invited to teach at UCLA where he remained until 2008.

While teaching, Baldessari remained a prolific artist. Many of his works demonstrate—and often combine—the narrative potential of images and the associative power of language. While they might take the form of parables, allegories, or "art lessons," they also show Baldessari’s fascination with jokes, dreams, aphorisms, sight gags, and linguistic pranks. In this way, his work lacks the austerity usually associated with conceptual art; instead, he uses light, absurdist humor, and materials that reflect the influence of Pop art.

Specifically, Baldessari uses photographs and text, or simply text, on canvas. The works are empty but for painted statements derived from contemporary art theory, such as A Two-Dimensional Surface Without Any Articulations Is A Dead Experience (1967). To emphasize the objective use of language, Baldessari hired sign painters to produce the works in a plain black font. The flatness and directness of Baldessari’s words, photographs, and paint result in ironic visual statements aimed at the very definition of art.

Accordingly and amusingly, his works often feature statements that set out to define the most elusive questions artists confront. For instance, What is Painting (1968) tries to define the art form in three short sentences taken from a book about art appreciation. This painting of words ironically ends with “Art is a creation for the eye and can only be hinted at with words.”

Text began to disappear from Baldessari’s work in the early 1970s. He made a number of experimental works using photography, such as sequences showing attempts at accomplishing an arbitrary goal. They include Throwing Three Balls in the Air to get a Straight Line (1973), which shows Baldessari aiming to do just that. Since then he has generally relied on collage. Typically, Baldessari pieces together apparently unrelated pre-existing images to force the viewer to recognize the similar messages those images communicate. Moreover, he distorts them, challenging us to consider how and what the images are communicating.

In particular, Baldessari began using price stickers—bright primary colored circles—to conceal individual faces. Yellow, red, and blue dots (eventually evolving into various rounded shapes) that cover faces and body parts would become Baldessari’s signature. In so doing, his imagery would veil expressive content and draw attention to minor details and the negative space between them. Works such as Frames and Ribbons (1988) and Stonehenge (With Two Persons) (2005), which feature bright circles over the subjects’ faces, emphasize the banality of certain social rituals, such as award ceremonies and tourist traps, respectively.

In the early 1970s, Baldessari produced a series of videotapes in which he conducted ironic investigations and droll conceptual exercises on the subjects of art and knowledge. In the video I Am Making Art (1971), he stands facing the camera and makes several arm movements—crossing his arms over his chest, swinging an arm out to one side, or pointing directly at the lens, for example—then recites the phrase, "I am making art," after each gesture. Thus, he associates his choice of movements with the artistic choices that a painter or sculptor might make. His video also implicitly asks how much art can be reduced before it stops being art at all. Baldessari also comments on formalist assessments of art in How We Do Art Now (1973). In one segment of the video entitled "Examining Three 8d Nails,” he obsessively details the nails, noting their descriptive qualities in an effort to indicate which nail appears "cooler, more distant, less important" than the others.

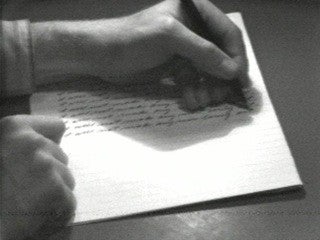

The video I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971) continues in this vein. Prior to its production, the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design invited Baldessari to exhibit his work. Unable to fund his own trip to Canada, Baldessari sent instructions instead of art. In a letter, he asked that student volunteers to write the phrase “I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art”—based on a sentence Baldessari had written to himself in a notebook—on the walls of the gallery and continue every day, if possible, for the length of the exhibition. Inspired by the work’s completion, Baldessari recorded his own version on videotape, in which he dutifully writes the line over and over again in a notebook for more than half an hour. The resulting work exemplifies Baldessari’s ability to use irony and humor to comment on larger concerns in the art world. While the statement reflects his dissatisfaction with painting in the early 1970s, its repetitive, mundane inscription comically conflicts with his goal—to not make boring art. — Kanitra Fletcher