American artist Kehinde Wiley (born February 1977 in Los Angeles, CA) is best known for his colorful, monumental, and elaborately patterned portraits based largely on Old Master paintings of heroic figures, the status of which Wiley confers onto contemporary black male subjects. He earned a BFA in 1999 from the San Francisco Art Institute and an MFA in 2001 from Yale University. In 2015, Wiley was the recipient of the National Medal of Arts. He currently lives in New York City and Beijing.

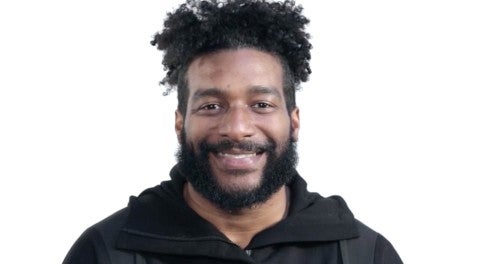

In 2001, Wiley was an in artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem. During that time, he found a discarded New York City Police Department mug shot on the sidewalk and was taken by the blunt presentation of the young black man depicted in the image. Wiley then began to consider issues surrounding the control of one’s own image in portraiture. He also would continue to be inspired by future encounters on the street. That is, the majority of his paintings depict models he has found through “streetcasting.”

Wiley approaches passersby whose looks he likes and invites them to his studio to peruse art history books and select a character in a painting of their choice to serve as source material for a portrait. The visual rhetoric of power, dignity, and heroism in artwork by painters such as Raphael, Titian, Tiepolo, Ingres, and Sargent provides inspiration for the representations of the urban black and brown men Wiley has met across the globe. At the same time, these figures are presented in imagery that is not necessarily coded as masculine—including decorative elements from Islamic, Rococo, Baroque, and other types of design, which Wiley calls “floration”—and sometimes undeniably has homoerotic undertones.

Beyond the sociopolitical implications of his oeuvre, Wiley has stated that he tries to “create a type of work that is at the service of [his] own set of criteria, which have to do with beauty and a type of utopia that in some ways speaks to the culture [he is] located in.” Thus, as his work questions the cultural narrative of the Western art canon by replacing conventional images of white men of historical status with contemporary men of color, it also disrupts and re-presents notions of black beauty, masculinity, and sexuality.

Wiley’s breakthrough came from his Passing/Posing series, produced between 2001 and 2004, in which young black male figures dressed in streetwear replaced the heroes, prophets, and saints of Old Master paintings. The following Rumors of War series from 2005 displaced Velazquez’s, Rubens’s, and others’ depictions of heroic equestrians with contemporary men wearing team jerseys and Timberland boots, but retained the original titles. Colonel Platoff on His Charger (2007–08), for example, features a young black man who looks directly at the viewer as he sits atop a charging white horse. However, rather than a black uniform festooned with medals, as seen in the original painting from 1815 by James Ward, Wiley’s model wears green cargo pants, yellow Nike sneakers, and a red jacket with a fur-trimmed hood. The scene takes place within a barren field surrounded by not only swirling white clouds but also a collection of white vines of fleur-de-lis that whirl throughout the canvas and frame the rider.

In the 2008 Down series, Wiley produced eight grand-scale paintings of black male figures in prone and reclining postures that reproduce those seen in works based on iconic images of fallen warriors in art—from bullfighters to Christ—such as Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Dead Christ in the Tomb and Auguste Clésinger’s Woman Bitten by a Serpent. Down is said to represent the inevitability of failure that is rarely acknowledged in, but often accompanies, most heroic acts. The title also is a play on words that has multiple meanings, including the pose of the figure lying down, the situation of being “down and out,” and the sexual reference of being on the “down low.”

Wiley followed Down with his World Stage series, which took him to Nigeria and Senegal (2008), Brazil (2009), India and Sri Lanka (2010), Israel (2011), France (2012), Jamaica (2013), and Haiti (2014). These portraits feature black and brown male and female sitters in poses based on traditional European paintings in front of vibrant, intricately patterned backgrounds. In 2012, he devoted an entire series to black women, An Economy of Grace. As depicted in the film of the same title that documents the making of the series, Wiley paints and sculpts imagery of six women he met on the street in Brooklyn in costumes commissioned from the French fashion house Givenchy, surrounded by ornate floral backgrounds.

It is fascinating to consider the considerable evolution of scale and production in Wiley’s practice when watching the video Smile (2003). However, the artist’s core longstanding interest in the control and perception of black bodies has been apparent throughout his career. In Smile, Wiley challenges four (out of seventeen) black men at a time, each presented in a separate quadrant of the screen, to smile directly into the camera’s lens for one full hour. Eventually the smiles contort, muscles spasm, and cheeks and lips start to quiver or seize. When a man can no longer smile, a new man immediately replaces him in the grid.

Obligated to appear happy, the men in Smile suggest the struggle and vulnerability behind maintaining a certain appearance in daily life. They also speak directly to the challenge of viewers and a culture in dealing with perceptions of young black men. Who wants them to smile? Whose comfort or happiness is of concern? As the men suffer from their expressions, Wiley’s video implicates the viewer in their pain. Furthermore, like his later portrayals of black and brown bodies in an art historical tradition that has depended on the domination of similar bodies, Smile viscerally demonstrates Wiley’s admission that his artwork creates “an uncomfortable fit… [but] that discomfort is where the work shines best.” —Kanitra Fletcher