Mona Hatoum's life and work consistently defy the notion of identity as something fixed and easily definable. Accordingly, she has developed a wide-ranging oeuvre that includes sculpture, video, installation, photography, performance, and works on paper. Hatoum’s art offers multiple perspectives and frames of reference, both formally and conceptually, thereby echoing the discord of her personal and cultural histories.

In 1948 Hatoum’s Palestinian family fled its home in Haifa during the Arab-Israeli War and settled in Beirut, where Hatoum was born. Because Palestinian refugees were denied citizenship, Hatoum’s father attained British citizenship for his family through his job. Years later, in 1975, while Hatoum was traveling in the United Kingdom, the Lebanese Civil War broke out, preventing her from returning home. She took advantage of her situation to fulfill her dream of studying art. Hatoum earned a degree from London’s Byam Shaw School of Art and, as the civil war escalated, she continued her studies as a graduate student at the Slade School of Art. She now splits her time between London and Berlin.

While Hatoum’s art is informed by personal experiences, it is rarely autobiographical. Rather, she uses her past as a way to reflect on larger themes of power, violence, surveillance, and racial and gender politics—widespread concerns that cut across cultural divides. In the 1980s, her involvement with feminist and political action groups led to confrontational performance works that intensely focused on the body. Her risk-taking and physical distress spoke to the vulnerability and violence produced by institutional power structures. In particular, the overtly political The Negotiating Table (1983) featured Hatoum lying on a table beneath a spotlight. Wrapped in plastic and gauze, bound by rope at her feet, and covered in blood and entrails, Hatoum remained motionless while excerpts from speeches about peace filled the space.

By the mid-1990s, Hatoum’s practice had shifted from performance to formally austere, minimalist sculptures and installations, which nonetheless viscerally evoked the body and its relation to various cultural politics. In fact, Hatoum employed bodily material, particularly her own hair, in many of these works. In Jardin Public (1993), the seat of a chair displays a triangle of her pubic hair. In Traffic (2002), two suitcases sit on the floor, attached by a thick mass of human hair. The latter piece suggests layers of meanings, such as the personal baggage we carry with us and the connections we make as we move through different spaces and contexts. It also conveys the control, silencing, and even trafficking of human bodies.

Utilizing the body in another unexpected manner, Hatoum produced her signature work Corps Étranger (or Foreign Body) in 1994. She underwent an endoscopy and colonoscopy, projecting the resulting video onto a darkened floor. The viewer looks over and into Hatoum’s enlarged body as the camera passes over skin and enters orifices. The device continues to travel through the tunnels of her body, offering a repulsive, yet fascinating, commentary on issues of surveillance.

Hatoum is also well known for her sculptures of furniture and domestic objects transformed into threatening counterparts, which, in Hatoum’s view, “by implication…make reality itself questionable and full of uncertainties." Indeed, Marbles Carpet (1995), an installation in which the gallery floor was covered with thousands of glass marbles, suggests that the viewer is (literally) standing on shaky ground, uncertain of her or his place in the world. Silence (1994), a nearly invisible infant's crib made of glass, and Marrow (1996), a children's cot formed from rubber and consequently shown collapsed on the floor, also speak to the fragility and impermanence of the body.

Hatoum also suggests the perils of domesticity in Doormat II (2000–01), a mat that states “Welcome,” but is composed entirely of hard metal pins, and Grater Divide (2002), a six-and-a-half-foot-tall kitchen grater. The work’s size transforms it into a room partition, but its sharp edges threaten to harm those who dare to cross to the other side. As Hatoum explains: “Home and the uncanny, or the familiar turning unfamiliar, is the basis of so many of my works. Whether playing with scale…or using incongruous materials that make the objects or furniture unusable or dangerous, this is all about the uncanny.” Undoubtedly, these interests largely result from Hatoum’s experiences of the instability that can intrude upon domestic security despite or due to political unrest.

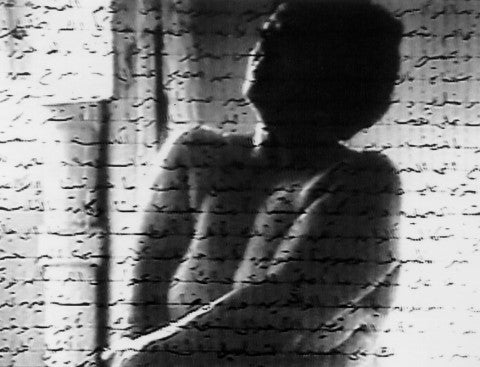

Those events and the complexities of war, exile, and displacement are evoked in Measures of Distance (1988), in which a recording of an animated conversation in Arabic between Hatoum and her mother is overlaid by Hatoum's somber voice slowly reading her mother’s letters in English. The written Arabic script of the letters covers the frame and acts as a screen, both concealing and revealing a series of nude images of the mother.

During a visit to Beirut in 1981, Hatoum recorded a discussion with her mother about sex and sexuality. To her father’s dismay, she also photographed her mother in the shower. Despite his disapproval of "women's nonsense," in her letters, Hatoum's mother fondly recounts the visit. She also expresses her longing to see her daughter again as she relates incidents that convey the danger and anguish of daily life in Beirut.

Although Hatoum and her mother are far apart, Hatoum’s use of video produces an intimate account of their history and relationship. The layered presentation of the sight, sound, and script of her mother creates a presence that effectively intertwines the two women in an imaginary, multidimensional moment. Ultimately, the cultural and geographical distances between mother and daughter collapse as do those between their personal experiences and the political concerns of a wider public. —Kanitra Fletcher