Over the past three decades, Shahzia Sikander (born 1969 in Lahore, Pakistan) has developed an interdisciplinary practice that includes painting, digital animation, video, performance, murals, and installation. Nonetheless, she explains, “Drawing is a fundamental element of my process—a basic tool for exploration. I construct most of my work, including patterns of thinking, via drawing.” Observers of the evolution of her practice, therefore, can detect some evidence of Sikander’s hand and process despite her involvement with various technologies. Moreover, the directness of the encounter between ink and paper complements the immediacy of her representations of disruption, transformation, and displacement regarding a range of subjects, from personal identity to global economic structures.

Sikander strengthened her skill in drawing when she was a student at the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore, where she earned her BFA in 1991. At the NCA, Sikander began the traditional practice of Indo-Persian miniature painting at a time when it was extremely unpopular among young artists. Nonetheless, Sikander, who came to miniature painting from a background in mathematics, Sikander saw the genre as an “incredible puzzle” she wanted to analyze. Her interest was based less on narrative and iconography and more on abstract aspects—line, light, color, and space—and its formal structure.

Sikander’s analysis of miniatures led her to transform the genre into a contemporary style with her breakthrough work, The Scroll (1989–90). She combined several scenes of a personal narrative—the daily life of a young woman as she moves through various spaces in her home, engaging in a range of activities, such as reading, cleaning, eating, and painting—into a single five-foot-long frame, rather than producing traditional single-page paintings that illustrate religious or mythological themes. Sikander received critical acclaim for The Scroll in Pakistan. She won the Shakir Ali Award, the NCA’s highest merit award, and the Haji Sharif award for excellence in miniature painting. Sikander also single-handedly reinvigorated a genre that numerous Pakistani art students began to embrace in the 1990s.

Sikander then relocated to the United States to study at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). She developed a practice of precise, detailed drawings and merged traditional elements of Islamic art and miniature painting with modern techniques and abstract designs. In 1995, she received her MFA from RISD and entered the Core Program at the Glassell School of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where she began experimenting with the site and scale of her work. Sikander drew enlarged images directly onto the wall. Effectively murals, these works altered her style and technique of mark-making as they generated new associations for the various forms pictured.

In 1997, Sikander relocated to New York City and was featured in the Whitney Biennial as well as a solo exhibition at the Drawing Center in New York. Numerous shows have followed at The Renaissance Society, Chicago (1998); Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. (1999); Whitney Museum of American Art at Phillip Morris, New York (2000); Asia Society, New York (2001–02); Seattle Art Museum, Seattle (2003); Miami Art Museum, Miami (2005–06); Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia (2006); Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, New York (2009); Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain (2015); and Honolulu Art Museum (2017), among other venues. Her work is included in numerous collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; and Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. She also has been the recipient of several awards, including a Tiffany Foundation Grant (1997), The National Pride of Honor by the Pakistani Government (2005), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Achievement Award (2006), and the inaugural Medal of Art by the U.S. State Department (2012).

In the late 1990s, Sikander expanded her wall drawings by layering them with a collection of surreal images, such as floating white veils and headless, armless silhouettes of female bodies with tendrils as feet, drawn on multiple sheets of translucent tissue paper of various lengths. She hung the papers several inches to feet away from wall to create three-dimensional works that reveal and conceal imagery as the viewer moves through the space. In this way, for Sikander, the tissue-paper works suggest “a certain sense of meaning being either manipulated or meaning being constructed, or that there is more to understand than a simplistic reading of something.”

This manner of disruption and alteration also is at the heart of Sikander’s practice. As a way to destabilize historical and political narratives, she explains, “I’m interested in taking a form, breaking it apart, and then rebuilding it. It is about transformation for me—whether it is the transformation of an image or a mark or a symbol or if it’s a transformation of a genre or transformation of a medium.” Thus, in 2001, while an artist-in-residence at ArtPace in San Antonio, Texas, Sikander introduced dimensions of motion and sound in her art and began working in digital animation. She continued to create tightly controlled images with geometric patterns, surreal shapes, and vivid colors, often set within or against intricate Indo-Persian borders and backgrounds, but now her various forms and characters were set in motion.

To animate her work, Sikander scans and digitizes her drawings with a high-resolution scanner and then mobilizes the imagery using animation software. As the figures move and morph on the screen, Sikander further destabilizes the space of miniature. Something that represented order and tradition becomes chaotic and contemporary. Her animation effectively breathes life into forms that mutate and detach from familiar references or traditional meanings, and the interactions among and relationships between them allow for multiple interpretations.

Sikander’s first animation, Intimacy (2001), which is approximately four minutes long, features text, animals, human figures, a rotating spiral, and other abstract forms, which appear and disappear. As the cast of characters enter and leave the frame at various points, Intimacy makes visible the mechanics and various phases involved in creating the forms.

SpiNN (2003) features the abstracted black hairdos of Gopi women (devotees of the Hindu god Krishna) that swarm and spiral like bats across the screen and into an image of a Mughal durbar hall. As the king’s court is a traditionally masculine space, the invasion of the floating forms serves as a pointed, feminist, and revolutionary, yet subtle and elusive, gesture, typical of Sikander’s art.

Parallax (2013) also features the Gopi “hair-birds,” as well as other forms from Sikander’s visual vocabulary, in a fifteen-minute, three-channel video animation. Made for the 2013 Sharjah Biennial, the work alludes to geographical, historical, and political aspects of the United Arab Emirates and global maritime trade. Sikander scanned and digitally processed drawings based on maps and landscapes, which she combined with a range of abstract, dreamlike designs and figures, to refer to the Strait of Hormuz, located between the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf, a critical site of international trade and warfare. Also accompanied by a lush, layered audio track of human voices in recitation by composer Du Yun, Parallax powerfully represents themes of dominance and dissonance.

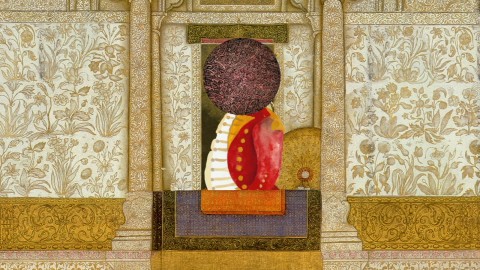

The Last Post (2010) conveys themes related to trade as well, as it reflects Sikander’s interests in the practices of the British East India Company in seventeenth-century Asia, which have had a lasting impact on the operations of corporate monopolies today. The animation specifically refers to the company’s presence in India and the opium trade with China as it follows a British officer who appears, disappears, and even shatters apart in a nonlinear narrative. Sikander presents this figure as a menace lurking through the architecture of the Mughal Empire in scenes juxtaposed with arrangements of surreal forms and designs, such as colorful floating disks, a rotating French horn, and spinning disembodied forearms. In a climactic scene, Sikander presents a monk balancing on a spherical collection of plant- and animal-like forms and toppling over to recall the “Last Post,” a bugle call that announces the close of a day of battle, commemorates the war dead, and, here, the collapse of British domination over China.

The gradual evolution of the scenes and various elements within them reinforces a sense of the long-established and continuing legacy of the colonial economy and the transformation of identities and cultures it entails, for better or worse. Du Yun’s jagged, enigmatic soundtrack further conveys a foreboding sense of the consequences of the East India Company, and Sikander ultimately implies such after-effects as the animation concludes. The officer appears as he did at the beginning, against a Mughal façade, but with his face obscured by an intricately designed sphere. The Last Post thereby suggests the last does not necessarily mean the end. —Kanitra Fletcher