Despite her tragic familial past, Brooklyn-based Nigerian artist Zina Saro-Wiwa focuses on work that reveals the creative, generative, and imaginative aspects of her background and homeland. Her father, Ken Saro-Wiwa, was a writer and activist who fought for human rights and against environmental degradation from oil exploration in the Niger Delta. He was murdered by the Nigerian military dictatorship in 1995. Saro-Wiwa sees herself not as an activist, but as a “culture-worker.” Although she addresses the people, culture, landscape, and traditions of the Niger Delta, like her father, she employs art (instead of political protest) to offer alternative views of the region that reject tired narratives related to the ravages of the oil industry. While it is true that oil extraction has had a major impact on the area, Saro-Wiwa endeavors to show us the limitations of such pessimistic narratives by presenting her birthplace Ogoniland, to which she returned in 2013, as fertile and dynamic.

She explains how artists make powerful change: “We can point the way to what’s actually there in the world, we change our value systems, we can create new industries, or the basis for new industries. That’s what art and artists can do. And that’s what I’m trying to do in Nigeria.” Accordingly, Saro-Wiwa opened a contemporary art gallery called Boy’s Quarters in her father’s former office building in Port Harcourt, where she exhibits the work of Nigerian and international artists. Her own work has been shown in solo exhibitions at the Blaffer Art Museum, Houston, and the Krannert Art Museum, Champaign, Illinois. Saro-Wiwa has been included in group shows at the Menil Collection, Houston; Seattle Art Museum; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; New Museum, New York; Brooklyn Museum; Tate Britain, London; Guggenheim Bilbao; UCLA Fowler Museum; and Prospect. 4, New Orleans. She also was the 2016–17 Artist-in-Residence at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, and received a Guggenheim Fellowship for Fine Arts in 2017.

Before pursuing a career as a photographic and video installation artist, Saro-Wiwa was raised, educated, and employed as a journalist in Britain. She studied economic and social history at the University of Bristol and was a reporter, researcher, presenter, and producer at the BBC, where she co-hosted the arts magazine program The Culture Show. At the BBC, Saro-Wiwa also produced and directed documentaries, including Bossa: The New Wave (2002) and Hello Nigeria! (2004). In 2008, she directed This is My Africa, a documentary featuring London-based Africans and Africaphiles, including Yinka Shonibare, Chiwetel Eijefor, John Akromfah, and Colin Firth, who offer their own anecdotes and commentaries on African culture, creating a wide-ranging exploration of the subject. The film eventually was licensed by HBO and shown at numerous venues, including the New York African Film Festival, Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town, Newark Museum, Brooklyn Museum, and the International Black DocuFest, where it won the award for Best Documentary Short.

Saro-Wiwa’s filmmaking evolved into a more conceptual style that led to the “alt-Nollywood” movement. Works associated with this genre are low-budget films that appropriate the tropes and subvert the conventions of Nollywood films. Phyllis and The Deliverance of Comfort (both 2010) were conceived during this stage in Saro-Wiwa’s career. Saro-Wiwa summarizes the former as “a meditation on loneliness and mental health.” This narrative-less portrait of a young woman also alludes to the practice and significance of wig-wearing in Nollywood films. The Deliverance of Comfort takes a satirical look at the belief in child witches in rural parts of Africa. Both works appeared in an exhibition that Saro-Wiwa curated at Location One Gallery in New York. Titled Sharon Stone in Abuja, it also featured the work of Wangechi Mutu, Pieter Hugo, and Mickalene Thomas.

Saro-Wiwa would continue to make films and videos after her move back to Port Harcourt, but in a less ironic manner. Her work from 2013 onward emphasizes the richness of the religious rituals, masquerade traditions, and culinary culture of the Niger Delta. Karikpo Pipeline (2015), for example, is a five-channel video of men dancing a masquerade in colorful elaborate costumes and antelope masks around decommissioned pipelines and land where pipelines previously existed. Their lively, acrobatic performance over areas once considered possessed by residents, or inert and exploited by foreigners, serves as a form of reclamation and regeneration. Saro-Wiwa presents what has always been present in the region—a life and culture that is light, vivid, playful, and at times contemplative.

Saro-Wiwa’s work also shows her ability to access aspects of Nigerian culture and community that are regularly hidden from view. The video installation Prayer Warriors: The Survival Performances (2016) features pastors preaching and singing in Ogoni in a dynamic, kinetic visual format. These preachers typically come to people’s homes to pray with them and to connect with the spiritual realm as a means of survival in difficult socio-economic circumstances. However, in Prayer Warriors, the preachers generously and forcefully present their practice to a wider audience. Saro-Wiwa also made a series of photographs entitled Men of the Ogele (2014), which depicts fully and partially unmasked Ogele masquerade performers. The men of the Ogele have never been photographed before and they are difficult to track down, as they move around villages of Ogoniland or are hired for special occasions and political rallies. Saro-Wiwa’s series gives viewers a rare glimpse into the humanity and humility of these elusive performers.

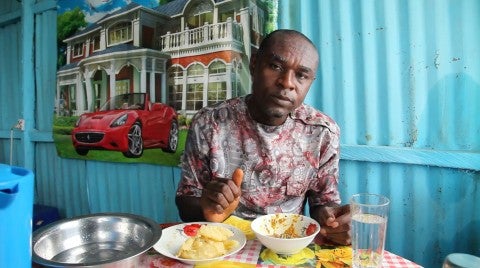

The humanity of Ogoni people also is asserted in Saro-Wiwa’s Table Manners (2014–16). This work comprises a series of videos, each titled with the name of a person and a dish they will eat, such as “Victor Eats Garri and Okra Soup with Goat Meat.” Saro-Wiwa next shows a person seated at a table with a full plate of food in a local restaurant or other setting near his or her home in the Niger Delta. The subject then simply eats while looking directly into the camera (and effectively at the viewer) until she or he consumes the entire dish.

These ordinary acts powerfully and wordlessly relate to the complex issues and histories of the region as well as to the viewer, who essentially shares a meal with each diner. The direct looks of the diners deny voyeurism and confront colonialist fascination with, or disparagement of, the ways African people eat, as the sitters reject so-called proper “table manners” and feast on their meals with their hands. Furthermore, Saro-Wiwa’s videos celebrate the rich, locally grown produce of the Niger Delta with dishes traditional to the area, such as egusi soup, roasted ice fish with mu, cocoyam with palm oil, and garden egg with groundnut butter.

Table Manners challenges pessimistic views of Africa as lacking or replete with starvation and malnutrition. These simple, straightforward videos of Ogoni people eating speak to the active farming and fishing culture that persists in the Niger Delta despite the exploitative practices of the oil industry as well as the subsequent sensual pleasure of cooking and eating its bounty. Moreover, Saro-Wiwa’s work demonstrates the ways in which art can make elements of everyday life powerful tools for cultural understanding and social transformation. According to the artist,

Nothing is more immediate than food, than the act of nourishing the self. I have found working with food the most strangely powerful and useful way to subvert and renew the conversation about the Niger Delta which defaults to this very circular, bleak handwringing which has led to very little change or insights into who we really are as a people and how to transcend our predicament. Food has been my portal to accessing something elemental and mysterious but generative and powerful. And the way art reframes an idea or a place is often the embryo for change.

—Kanitra Fletcher