Much of Mikhail Karikis’s (b.1975, Thessaloniki, Greece) body of work addresses marginalized groups and the ways in which the voice, viewed as sculptural material, can be used as a tool of empowerment and possibly an agent of social and political transformation. Rather than intelligible language, Karikis frequently focuses on preverbal, nonsensical sounds, such as whistles, grunts, hisses, and sighs, noises that communicate emotionally and on a level beyond that of ordinary words. He then uses film to “contain, capture, document, and explore” these expressions and emphasize how they evoke strong emotional associations and figure as acts of resistance.

Karikis studied architecture at the Bartlett School before completing an MA and PhD at the Slade School of Fine Art. He currently lives and works in London. His work has been shown in solo and group exhibitions at Casino Luxembourg Forum d’art Contemporain (2017); Kochi-Muziris Biennale (2016); Leeds Art Gallery, UK; Witte de With, Rotterdam (both 2015); Hayward Touring, UK (2014-15); Palais de Tokyo, Paris; Tate Britain, London (both 2014); Tate St. Ives and Nottingham Contemporary, UK (2013-14); Manifesta 9, Belgium (2012); and the 54th Venice Biennale, Italy (2011). Karikis has performed at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden and Barbican Theatre in London, and his films have been shortlisted for the 2016 Film London Jarman Award, UK, and the 2015 Daiwa Art Prize, UK-Japan.

In 2010, Karikis began producing his “Work Quartet,” a series focusing on different generations of people and the relationships between the subjects and their work contexts as well as the theme of traveling as way of entering another realm, difficult situation, or impossible region. Karkikis has referred to the first film, Xenon (2010), as “a sort of toxic work in that it is very critical, punishing and polemical.” The artist met with a group of young workers his own age to contemplate power dynamics and the rights and suppression of speech at work. Their conversations provided the material for a 23-minute film in which several characters are shown in claustrophobic office spaces or dreamlike sequences. In the office scenes, they appear in uniforms of suits and ties to sing operatic notes, stomp their feet, or dramatically whisper, cough, and gasp. These scenes are juxtaposed with ones in which each subject acts out their frustrations of feeling trapped and unable to fully express oneself. A man performs awkward dance moves with balloons protruding from his unitard, a zombie like woman with beach balls strapped to her body bangs on a drum, and a violinist uneasily contorts himself as he plays strained, anxiety-inducing tones. The bodily sounds and movements along with the exaggerated settings create overwhelming senses of desperation and yearning for freedom to form “a critical political allegory reflecting on the global economic upheavals post-2008 and the state of human rights… [For Karikis,] the main question was: how can we express ourselves if the power of political speech and language has been hollowed out?”

Sounds From Beneath (2010–11) is decidedly more mournful, but no less political. Based in Kent, the film is a collaboration with a choir composed of former coal miners from the Snowdown mine, which was known for its terrible working conditions and closed in 1987. Stunning views of the dark, cracked earth that remains over the abandoned colliery are interspersed with scenes of the men standing in various formations that resemble picket lines as they hum work songs, chant the names of the tools, and replicate the drills blasts and other industrial sounds of their past excavations. Collectively, their powerful sonorous voices effectively revive the decimated landscape. Commenting on the film, Karikis stated “Sounds from Beneath was a kind of solution … where I explored the possibility of creating a political vocal gesture that was neither propaganda nor sloganistic speech. The miners vocalize something that is connected to the specificities of what they did, their memory and community, and at the same time they reclaim the political agency they were denied in their protests and strikes. Their abstract vocal acts are specific to their community and go beyond predictable political speech.”

In SeaWomen, the subjects are shown in their place of and at work—the volcanic island of Jeju near South Korea. Karikis collaborated with a vanishing community of 60 to 90-year-old fisherwomen known as haenyo (sea women) to document them diving without oxygen in dangerous waters for fish and pearls. As their dominance in the Korean economy has subsided substantially, with fewer and fewer young women willing or needing to take up such arduous work, what Karikis's film does retain is documentation of the high-pitched squeal or whistle the women emit during their expiditions. The soundtrack, so to speak, of the women fishing, resting, eating, and conversing is a sound simailar to that made by dolphins and whales that comes from a partcular breathing technique the women use to endure dives that can be up to sixty-five feet deep. Their emissions thus represent a dynamism and independence typically not attributed to elderly women, however, according to Karikis, “the old women’s bodies are active and powerful and represent a model of existence that gave me hope."

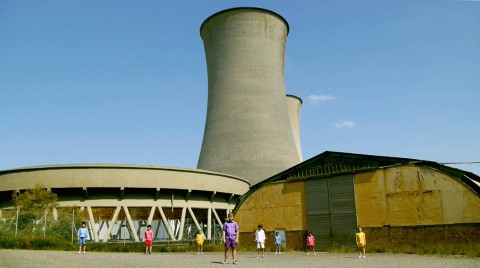

Likewise, Children of Unquiet (2014), the final film of the "Work Quartet," is unexpectedly hopeful as a response to Karikis’s “questions about the future: what do we leave to the next generation, how do we empower them to change things?” Instead of working with older men and women as he had done in his two previous projects, the artist engaged a group of young children, forty-five boys and girls aged between five and twelve, who effectively take over Larderello, Italy, an abandoned village in Valle Del Diavolo or “Devil’s Valley.” The area is known for its surreal, spectacular landscape of geysers and fumaroles that inspired not only Dante’s setting of his Inferno, but also those who established it as the site of the world’s first geothermal power plant. Architect Giovanni Michelucci soon constructed modernist villages to house the thousands of workers brought in to operate the plant. However, with the advent of automation in the early 1980s, major unemployment and then rapid depopulation swept Larderello.

Rather than view the deserted villages as hopeless, the children reanimated the environment by recreating the various geothermal and industrial sounds of the landscape, such the hiss of the geysers, gurgle of bubbling water, and roar of the factory pipes. They also read passages on productivity and love as a revolutionary force from Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Commonwealth. The film then concludes with them playing games—soccer, jump rope, pattycake—in abandoned buildings and around gravel pits, transforming the wasteland into a self-organized school and playground.

Dressed in brightly colored monochrome outfits, their appearance and activities are infused with joy and curiosity, transforming a site that seemed tragically scarred by capitalist forces. The children are not dismayed by its condition, rather they sing, play, and find ways to be in concert with the environment, constructing for themselves and offering viewers an optimistic alternative to the antagonistic relationship between the human and the earth that preceded them. -Kanitra Fletcher