Louise Bourgeois’ Eyes to Leave UT

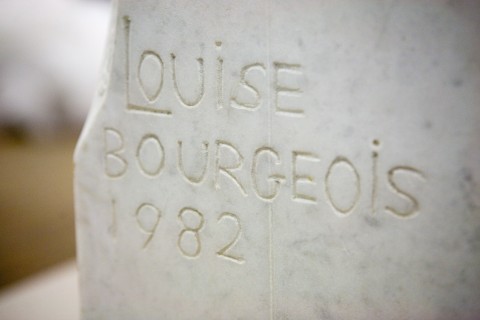

Later this month, Louise Bourgeois’ sculpture, Eyes, will be permanently removed from the atrium of Bass Concert Hall at Texas Performing Arts and returned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On view since 2008, Eyes is one of 28 works on long-term loan to Landmarks from the Met, and has greeted more than three million people while at the university.

Though the past few months have begun to signal a light at the end of the COVID tunnel, the pandemic has necessitated a number of changes that are here to stay. The use of physical spaces on campus—and the way our bodies move through them—has been extensively reconsidered. Sadly, it was determined that Bourgeois’ sculpture needs to be removed to allow space for new entrance protocols when Texas Performing Arts reopens to the public this fall.

We know that Eyes is a much-loved work in our collection. It has been the point of engagement for thousands of people on Landmarks tours over the years, and especially significant to our student Docents and Preservation Guild volunteers. If there were an alternative space on campus that could house the work, then we would certainly relocate it. Unfortunately, that is not the case.

Landmarks will create a virtual memory-board in honor of the work. We invite our followers to share photos or memories of the work to be included. Materials may be emailed to landmarks@austin.utexas.edu.

We thank you for your continued support of Landmarks and your enthusiasm for the works in our collection.

Memories from Landmarks Docents and Preservation Guild Members:

“I always really appreciated the piece’s location in Bass entryway. Placing an already large sculpture in a large atrium had a commanding sense of grandeur and attention. When giving tours, it felt like a piece deserving of a slow look, yielding new insights as you pursued further but also having enough tangible to immediately grab onto for less familiar viewers. The weight of the sculpture - both literally and figuratively - was also captivating to watch people navigate around, conveying art’s literal importance to how we navigate our day to day lives. From waiting in line to see a traveling musical to working as a PA for Jimmy Fallon’s show at Bass, the sculpture engrained itself into the performative fabric of a theatrical piece’s built environment. The eyes of the piece are special too - there’s something really exciting about waiting for the doors to open to a show and peeking in the windows to see two large eyes staring back at you.”

– Emma Rappold, (RTF; UT 2020) Former Docent

“While I never toured Eyes, I help run an Explore UT Landmarks booth near it, so rather than engaging viewers, I was able to witness a lot of different kids' first impressions. I feel like it was one of the best pieces in the Landmarks collection to get kids to connect with abstract art. Appropriately, I remember the eyes of the sculpture most. I only passed through Bass a handful of times, but the eyes of the sculpture were always there - whether I was passing through alone, or staring above a crowd of people attending a show. As an architecture major, I enjoyed engaging people on not only the collection pieces themselves, but how they related to their surroundings.”

– Chandler Householder (Architecture; UT 2021) Former Docent

“I remember learning how Eyes’ placement within such a public area was a big point of trouble for its conservation. I found that aspect of it very compelling, as most marble sculptures that come to mind are old and figural where I don't expect large amounts of cleanliness or a pristine surface due to their age. Bourgeois’ age when she was carving was interesting to me as I don't generally associate such a laborious process with someone older. So, while the subject or actual form may not have been revolutionary to me, it still had plenty for me to learn and be engaged by, and the work completely changed with subsequent viewings.”

– Drew Rappold, Current Docent and Preservation Guild Member

“During my years as a student docent, I always loved to include Louise Bourgeois’ Eyes in my Landmarks tours. In contrast to some of the more abstracted, industrial pieces in the collection, visitors of all ages intuitively connected with Eyes and the familiar, powerful associations the piece drew from: across many cultures, eyes are deeply symbolic sensory organs that invoke sight, omniscience, and clairvoyance. Eyes felt particularly at home in the Bass Concert Hall Lobby during my years on campus. Under the bright lights of the concert hall, the rough, unfinished marble base sparkled—reflecting, by contrast, Bourgeois’ extraordinary efforts in carving the carefully smooth eyes, not unlike how the great Renaissance artists used the very same Carrara marble to transform hard rock into soft folds of flesh. Positioned next to the glass entrance doors of the lobby, viewers often commented on how Eyes seemed to be looking out to the concert hall plaza directly at another Landmarks piece, Magdalena Abakanowicz’s Figure on a Trunk. Although Bourgeois’ sculpture is only of a pair of eyes and Abakanowicz’s is of a headless human figure—meaning they could not really “see” each other—I liked to imagine the two works to be in some sort of intimate dialogue. Abakanowicz envisioned her humanoid figures after seeking escape in her imagination from the loneliness and cruelty of her childhood during World War II, while Bourgeois’ Eyes too were a rumination on the abuse she witnessed as a child. Together, the two pieces, each created by strong women artists speaking to issues of personal identity and isolation in a detached world, seemed to find solace in each other.”

– Keya Patel (Art History, Plan II; UT 2019) Former Docent